For communities shaped by faith, the idea that every person bears the image of God is foundational. In Christian theology, this belief—often called the imago Dei (Genesis 1:27)—affirms that every human life carries inherent dignity, worth, and moral significance. That conviction makes dehumanizing language more than a social concern; it makes it a spiritual one.

Across psychology, history, and theology, there is a consistent lesson: when we stop seeing others as fully human, we lower the barriers that protect them from harm.

What Is Dehumanization?

Social psychologists define dehumanization as perceiving or portraying others as less than fully human. Research by Nick Haslam (2006) explains that this can happen in two primary ways:

– Animalistic dehumanization – comparing people to animals or denying them uniquely human traits such as moral sensibility or refinement.

– Mechanistic dehumanization – treating people as objects, tools, or machines, stripped of emotional depth and individuality.

Both forms deny something sacred: the fullness of personhood.

Studies show that when people describe groups as “monkeys,” “apes,” “less evolved,” “uncivilized,” or otherwise less human, they become more supportive of harsh treatment and collective punishment (Kteily & Bruneau, 2017). Albert Bandura’s work on moral disengagement (1999) demonstrates how reframing victims as less than human allows individuals to bypass moral restraint. In simple terms: when dignity is denied, cruelty becomes easier to justify.

For faith communities committed to loving one’s neighbor (Mark 12:31), this research carries sobering implications.

A Painful History: Colonialism and Slavery

History reveals how often dehumanization has been used to defend injustice.

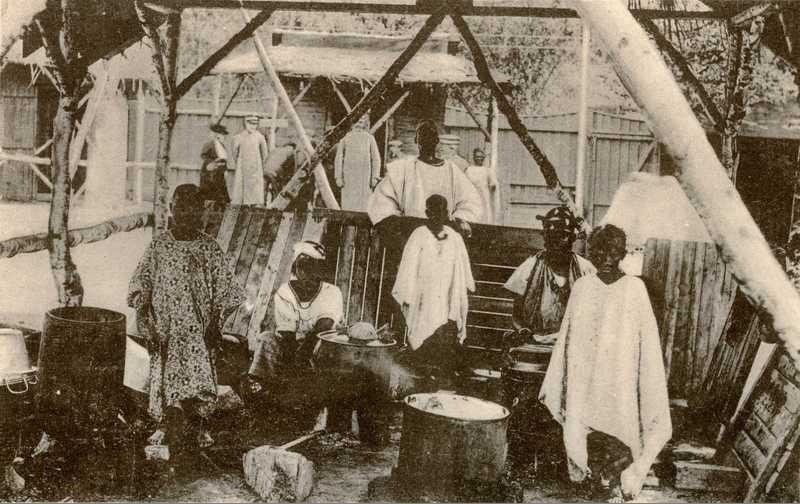

During European colonial expansion, Indigenous peoples were described as “monkeys,” “savages,” or biologically inferior. Black people were sometimes displayed in cages in Europe https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/16/belgium-comes-to-terms-with-human-zoos-of-its-colonial-past. Such language framed conquest as a civilizing mission rather than violent dispossession. Thinkers such as Aimé Césaire (1955/2000) and Frantz Fanon (1952/2008) argued that colonial systems depended on systematically denying the humanity of the colonized.

In the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved Africans were frequently depicted as animal‑like or naturally suited for bondage. Historian David Brion Davis (2006) documents how pro‑slavery theology and pseudo‑science worked together to rationalize exploitation. Orlando Patterson (1982) described slavery as “social death,” in which people were stripped of recognized personhood.

For people of faith, this colonial history demands humility. Scripture was often misused to justify systems that contradicted the biblical affirmation that all people are made in God’s image. Modern research shows the lingering effects of such imagery. Goff et al. (2008) found that implicit associations linking Black people with apes predicted greater acceptance of violence in simulated policing contexts. Dehumanizing metaphors do not fade harmlessly into history; they shape perceptions across generations.

Genocide and the Erosion of Moral Boundaries

The Holocaust offers one of the clearest examples of how dehumanization enables atrocity. Scholars such as David Livingstone Smith (2011) and Ervin Staub (1989) document how Nazi propaganda portrayed Jews as vermin or parasites. Anthropologist Alexander Hinton (2002) notes similar patterns across genocides: perpetrators first redefine victims as less than human. These patterns echo a biblical warning: when people are treated as objects or enemies rather than neighbors, violence escalates.

It is in this long history of dehumanization that we must view Donald Trump’s recent depiction of former President Barack Obama and his wife Michelle Obama’s heads on the bodies of apes in a jungle. This animalization mirrors earlier rhetoric in which he referred to immigrants as “vermin” or “animals.” Such language contributed to the justification of keeping immigrants in detention centers under horrendous conditions, because they were considered less than human and therefore undeserving of humane treatment.

Why This Matters for Faith Communities Today

Dehumanization rarely begins with violence; it begins with words, images, and small shifts in perception. Subtle forms—such as denying emotional depth to out‑groups (Leyens et al., 2000)—can gradually harden hearts. For communities shaped by faith, guarding language is not about political correctness; it is about spiritual integrity.

If every person reflects God’s image, then reducing anyone to an animal, a caricature, or a colonial stereotype contradicts that sacred truth. It erodes empathy, weakens the bonds of community, and dulls our responsiveness to suffering.

The consistent message across psychology, history, and theology is clear: seeing others as less than human makes injustice easier; seeing others as image‑bearers strengthens compassion and accountability.

In a polarized age, faith communities have an opportunity to model something different: speech rooted in dignity, disagreement without degradation, and conviction without contempt. To defend shared humanity is not only a social responsibility—it is an act of faithfulness to Scripture and to our calling as followers of Christ.

Picture credit: Africans exhibited at the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition in Christiania (Oslo), Norway, taken from : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jubileumsutstillingen_1914_OB.F08939d.jpg

Selected Sources

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Césaire, A. (2000). Discourse on colonialism. Monthly Review Press. (Original work published 1955)

Davis, D. B. (2006). Inhuman bondage: The rise and fall of slavery in the New World. Oxford University Press.

Fanon, F. (2008). Black skin, white masks. Grove Press. (Original work published 1952)

Goff, P. A., Eberhardt, J. L., Williams, M. J., & Jackson, M. C. (2008). Not yet human. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 292–306.

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264.

Hinton, A. L. (2002). Annihilating difference: The anthropology of genocide. University of California Press.

Kelman, H. C. (1973). Violence without moral restraint. Journal of Social Issues, 29(4), 25–61.

Kteily, N. S., & Bruneau, E. (2017). Backlash. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(4), 564–589.

Patterson, O. (1982). Slavery and social death. Harvard University Press.

Smith, D. L. (2011). Less than human. St. Martin’s Press.

Staub, E. (1989). The roots of evil. Cambridge University Press.

Be First to Comment